Villa Regina is a town located in Argentina's Rio Negro Province in northern Patagonia. Today it has about 30,000 inhabitants and is an important agricultural center known mainly for fruit production for domestic markets, but also for export.

In the late nineteenth century, in 1895, during the construction of the railroad southwest of Buenos Aires, Argentine President Julio Argentino Roca granted his secretary Manuel Marcos Zorilla 15,000 hectares of flat land on the condition that he would allow the railroad to pass through it.

With the intention of making these lands irrigated, in 1898 the government commissioned engineer César Cipolletti to make a plan to use the waters of the Neuquén, Limay, Negro and Colorado rivers; in 1907 construction work on the canals began. The engineer also presented his work in Rome in order to attract Italian investors.

A few years after his death, in 1923, his collaborator, engineer Felipe Bonoli, purchased 5,000 hectares of land from Manuel Zorilla's estate on behalf of the Compañia Italo-Argentina de Colonizaciòn, C.I.A.C., a joint public-private company. This was the beginning of the creation of the colonia and the city.

The initial capital of $1.4 million was used to purchase the land, which was leased in lots to settlers brought in at first directly from Italy, particularly from northern regions such as Friuli Venezia Giulia, and then, when emigration closed, identified among compatriots already living in the republic and among Polish and Czechoslovakian immigrants.

From Italy over 400 farming families were recruited and embarked for Argentina with the lure of quickly becoming owners of vast tracts of land that the company would assign to them.

On November 7, 1924, the colony was officially founded under the name Regina de Alvear, in honor of the Argentine president's wife.

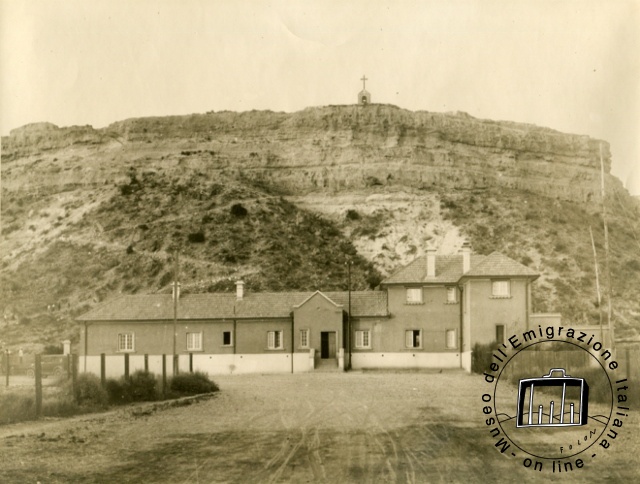

The settlers were given the land in return for a deposit of 10% of the total value of the land, delivered, as stated on the contract, plowed and fenced, and including a house with a porch, a bathroom and a well, and the taking out of a mortgage to be paid annually for the final redemption of the property.

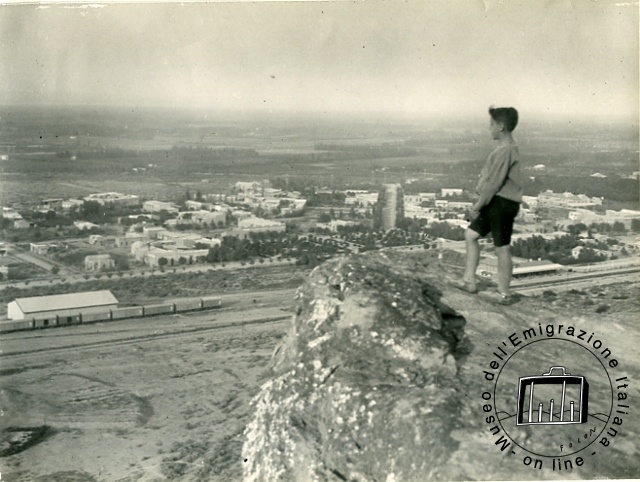

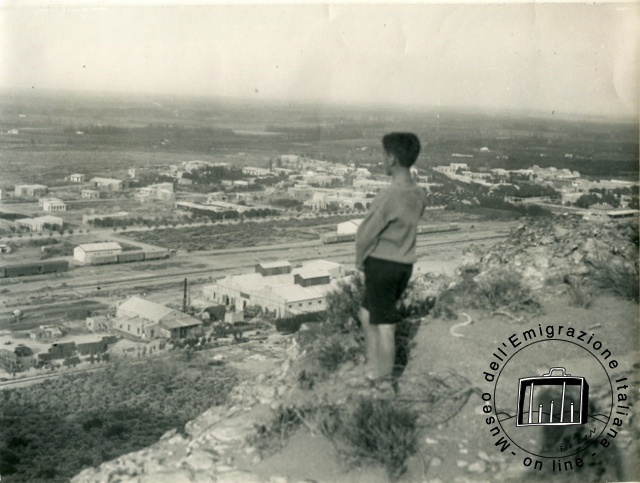

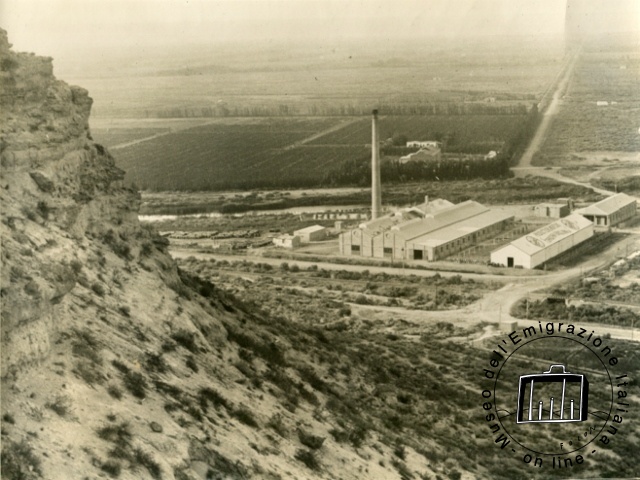

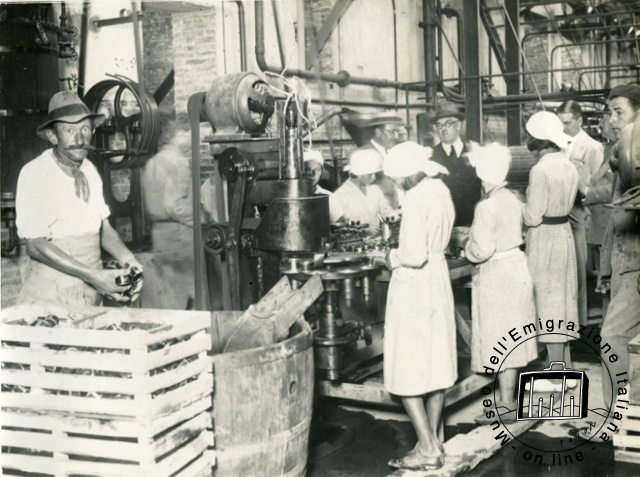

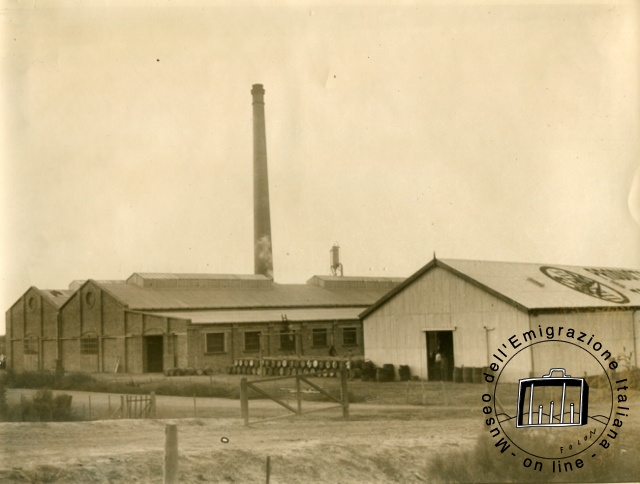

The colonization company had drawn up a development plan that included the cultivation of alfalfa, vineyards and fruit trees, with the plan to transform the land from arid and barren into an oasis of greenery, with very long rows of poplar trees bordering canals and roads, dotted with cottages and small industries for processing agricultural products and making wine.

The initiative constitutes fascism's first and unprecedented attempt at colonization with the creation of a "new city." This was an experience that a few years later would have important episodes in Italy, such as the foundation of Mussolinia di Sardegna in 1928 (today Arborea in the province of Oristano), Littoria (now Latina) and Sabaudia in 1933, Pontinia in 1935 (Agro Pontino) and others, as part of a more general project of reclamation of marshy areas and the assignment of those lands to veterans of World War I, through the administrative structures of the Opera Nazionale Combattenti. From an urban planning point of view, models of social organization and rural settlement, with the subdivision into estates and the creation of urban centers of aggregation that served as political and religious centers of reference, were experimented in Villa Regina, which would later be applied in the new Italian cities.

By 1927 Villa Regina had 1,000 inhabitants and thanks to a loan of 5 million liras from the Bank of Rome and other funding from the Italian Commercial Bank, a hospital, church, school, library and sports club were built.

A promising start to the colony's development was followed by a phase of severe hardship for the settlers who had dreamed of "making America" in Patagonia: local events such as the spread of malaria among the residents, the difficulty of cultivating brackish or high salt-soil, shortcomings in the establishment of an efficient marketing network for agricultural products and, not least, the international economic crisis of 1929, led the company almost to bankruptcy and the farmers to starvation. Many of Compagni's enticing promises that had determined the settlers' choice to leave had turned out to be untrue.

The C.I.A.C. had to mortgage the farms and also pledge as collateral the claims on those assigned. This was matched by a stringent recovery plan on the part of the banks, which went as far as evicting the insolvent settlers and putting the farms up for auction. The exorbitant interest on the mortgages taken out and the economic crisis effectively put many of the families who had come to Villa Regina only a few years earlier on the pavement.

Many immigrants thus found themselves, after selling their homes and land in Italy to embark on the Argentine adventure, landless and penniless in a foreign nation.

The protests of the increasingly desperate settlers, however, were not answered even by the appeal sent to Mussolini in 1934, nor did these succeed in moderating the appetites of the Company, which for about two decades continued the work of debt collection and, alternatively, the sale of the farms.

The protests of the exasperated settlers soon threatened to become full-fledged riots: unions and the Argentine church came to the defense of their rights.

Between the 1930s and 1940s, local Bishop Nicolas Esandi, a Salesian, became the bearer of the colonists' demands, attempting laborious mediations with the Company and the government partly in order to temper protests that could have turned into bloody riots. The tug-of-war between settlers and Company representatives often reached extremely high levels of tension.

Bishop Esandi's was a valuable work in defending the just claims of the dispossessed peasants and giving them confidence; he did not hesitate to intervene directly with the President of the Republic to urge settlement of the problem. An initiative that was artfully misrepresented by accusing the prelate of sobering the colonists to bring down the price of the farms and thus allow the Vatican to purchase, at knock-down prices, the Company's rights to the auctioned properties.

Only after the fall of Fascism and the end of World War II, in 1946, following a meeting between the bishop, a representation of the settlers and President Juan Domingo Peron was a way out of the long-standing and difficult dispute found: an extension of the period for the repayment of the land debt and the provision of subsidized credit for the construction of new housing.

The nightmare of eviction and the consequent loss of land and house, the result of renunciations, sacrifices, ended in December 1950 after more than twenty years of struggle, with the handing over of title deeds to the settlers. Many of the farms still continue their activities today and have turned into modern agribusinesses whose products carry the name of Villa Regina throughout the world.

Thus closed the page of a colonization experience of our emigrants in Patagonia, a painful but very beautiful page because it was written with the sweat of labor and inspired by the will to build a better life for themselves.

Pietro Luigi Biagioni, Marinella Mazzanti