Italian immigration to the United States, while largely composed of farmers, has stayed away from agriculture with exceptions in the southern states. Two names stand out above all others: Tontitown, in Arkansas, a colony with a troubled history, founded in 1898 and still a small town with a strong Italian component, and, in California, the Italian- Swiss Agricoltural Colony, founded in 1881 in Sonoma Valley, at the behest of Andrea Sbarboro from Liguria, forerunner of all the companies created by Italians in the "wine counties."

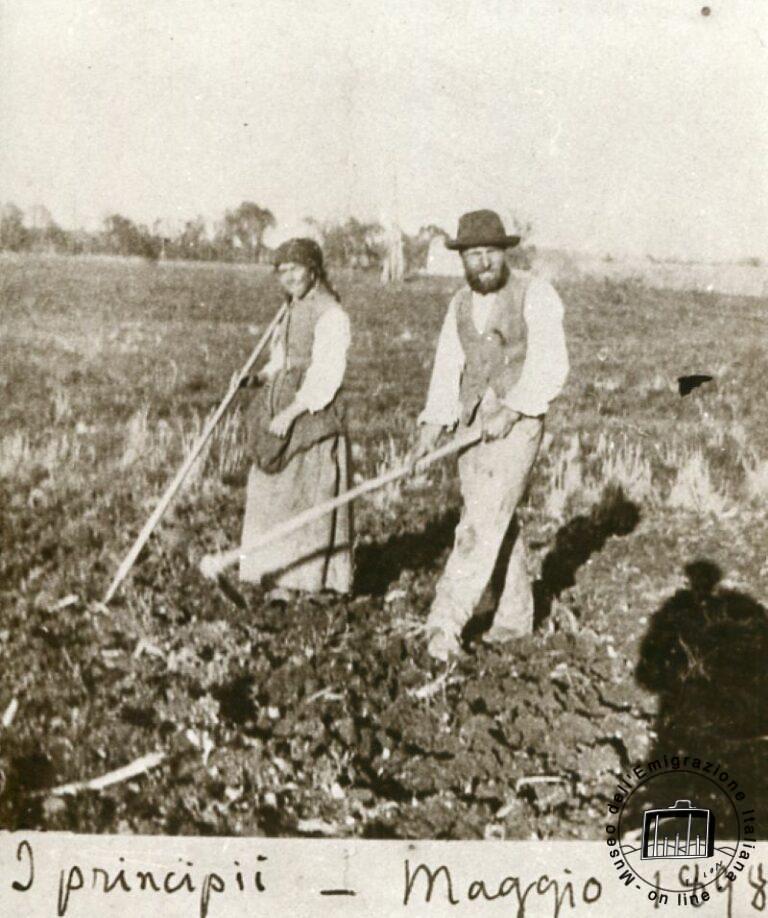

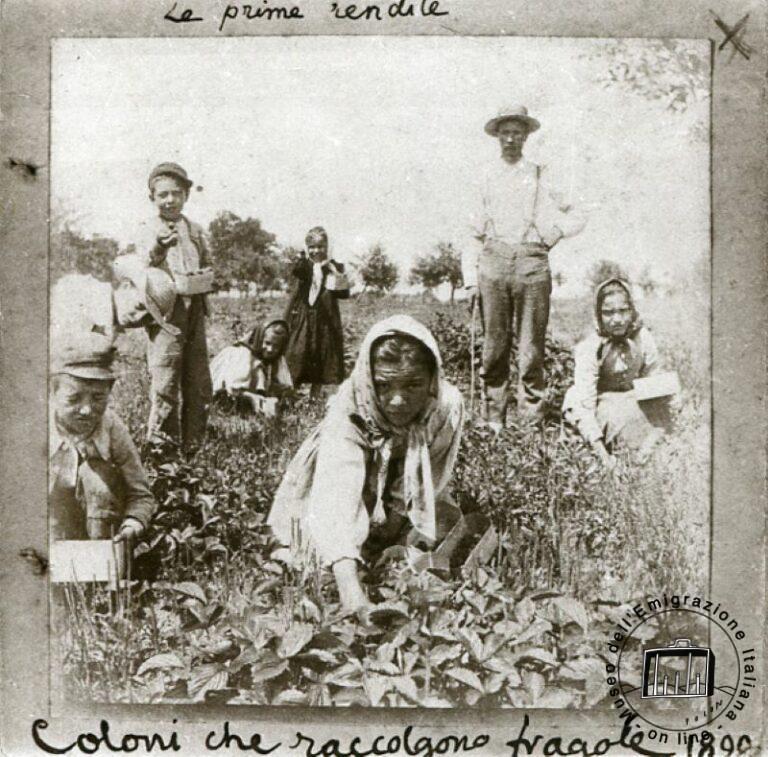

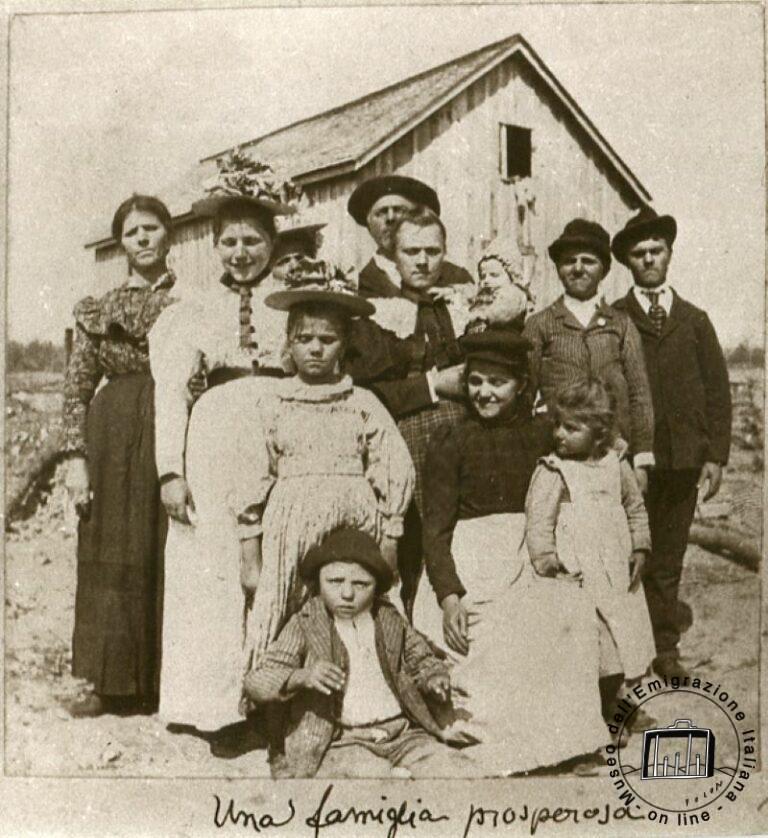

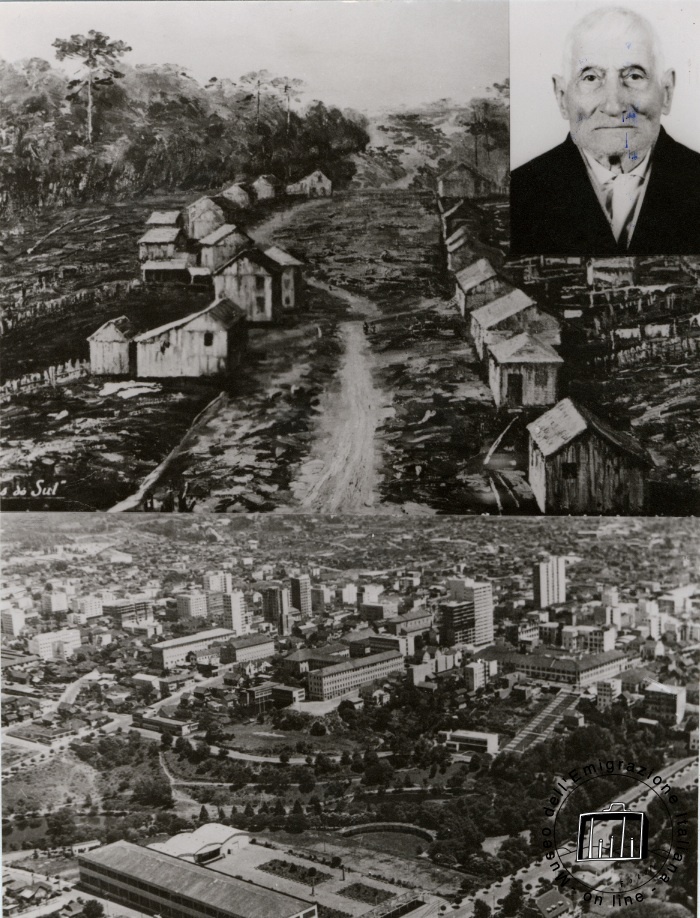

The situation in Latin America was different. In Brazil, in the states of Rio Grande del Sud, Paraná and Santa Caterina, farmers from Veneto, Friuli, Trentino and Lombardy founded colonial nuclei to which they gave the names of their countries of origin. Colonization was not easy even though aid and facilities were granted by the various state governments.

In Argentina one can take as an example Villa Regina, in the province of Rio Negro, where, with an expression that may seem rhetorical but is not, Italian settlers transformed the desert into splendid expanses of orchards and vineyards, of plantations of alfalfa, corn and various vegetables. The "secret" of this transformation was, in addition to the indefatigable work of the settlers, a grand irrigation system that was designed by engineer Cipolletti by harnessing the waters of the Rio Negro and other rivers in the area.

A singular path of several Italians has been that of town founders. It has sometimes happened that small entrepreneurs, working in the railroad construction industry, have had the intelligence to precede rather than follow the tracks and have therefore purchased parcels of land suitable for future stations, and the towns that would grow up around them, also planting sawmills for the production of sleepers and for the construction of shelters.

Having played a part in this genesis earned the protagonists the title of "city founders," which, in the boundaries and memory of the fledgling city, corresponds distantly to that of North American "pilgrim fathers." Not a trade, not a profession but a multifaceted activity related to the specificity and impermanence of the new frontiers.